Victorian Grandmothers

by

Sue Thring

Copyright 2008 by Prof M W Thring’s

executors.

All rights

reserved.

The cover features Lydia

Meredith in a watercolour painted by her daughter Annie in 1898.

INDEX

3 Foreword

4 Sarah

Jenkyns - my father’s great grandmother

13

36

58 Dorothy Wooldridge - my father’s mother

84 Margaret Sullivan – my mother’s mother

97 After-word

Appendix:

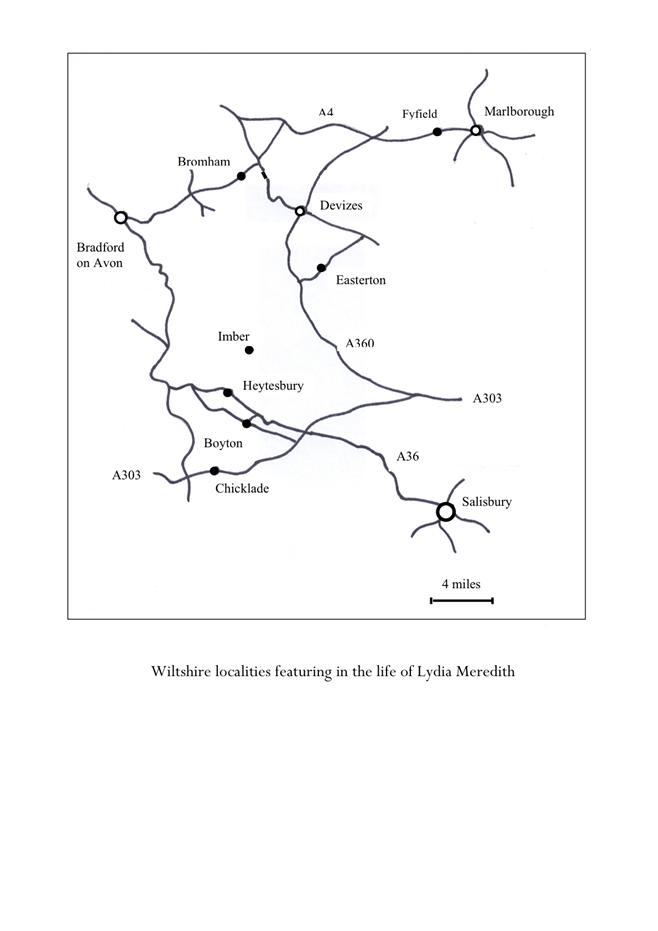

99 Map of Wiltshire localities featuring in the life of

Lydia Meredith

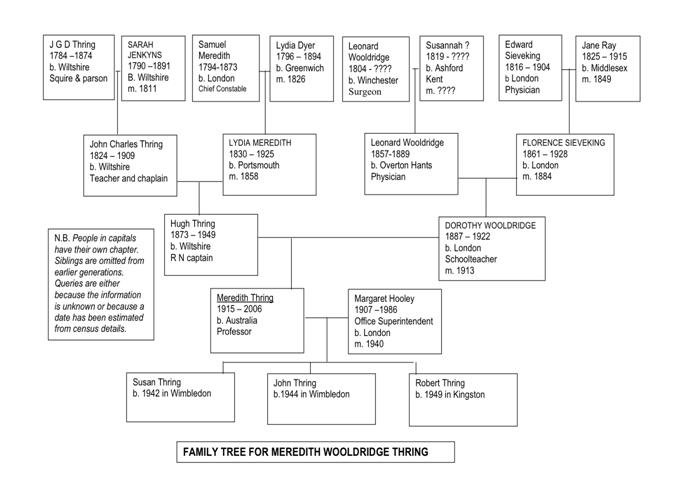

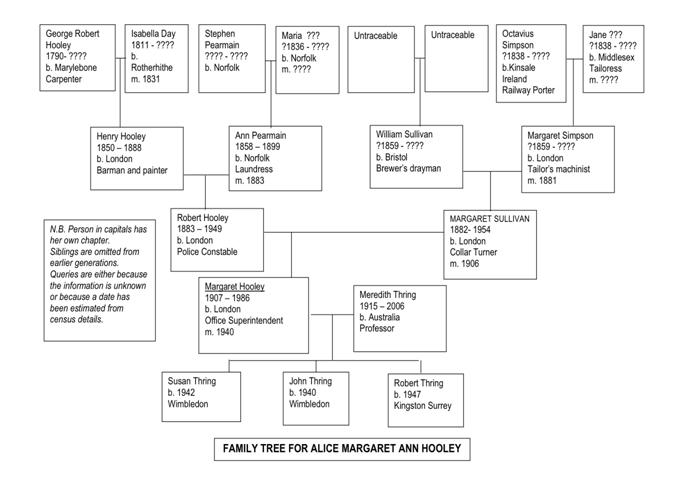

100 Family tree for my father’s family

101 Family tree for my mother’s family

102 Time line for my mother’s family

103 Time line for my father’s family

Contact suekal@thring.co.uk

FOREWORD

This has been

a labour of love. No – that’s only half

true; labour implies some misery and it has been pure enjoyment. The love has

been in the fascination with relating the lives of my ancestors to the

happenings of their times. Trying to

discover the individual habits, foibles and characteristics of my forebears has

also been a great interest.

It all started

from a vague curiosity. I realized that

although we had numerous facts about the men in my father’s family we knew next

to nothing about the women. On my

mother’s side we knew nothing of either the men or the women. By the time I was aged seven, three of my

four grand parents were dead, and in fact the only one I knew well died when I

was 11. This grandmother was, I realized

later, strangely reticent about her childhood and upbringing. So I missed out completely on the

grandparent-grandchild conversation along the lines of “what did you do when

you were a little girl/boy”?

As a woman

writing primarily for myself and for the, as it happens, all female next

generation I decided to explore the lives of the women and fit the men around

them in a reversal of the usual mapping of family history. However I hope that

my grandchildren will find it of interest when they are adult.

With the great

help of a friend, to whom very many thanks, one of the prime sources for family

information has been the Victorian census; collected every decade from

1841. Discussion with my uncle and with

my father’s cousins has been fascinating and profitable and my thanks go to

them too. Googling of family names has also been very fruitful. On my father’s side of the family, because

there were hoarders in several generations, a large number of letters,

photographs, books, newspaper cuttings and other interesting paper work have

survived. I have thus had enough

evidence to make informed guesses at the personalities and characteristics of

some of my Victorian relatives. However on my mother’s side of the family there

are just names and dates with no hint as to their characters and

interests.

In an appendix

are two simplified family trees and two time lines to try to relate consecutive

family and historical events. There is

also one map. At the beginning of each

section are lists of important dates, which include details of the relevant

siblings and offspring.

Obviously I

have only two grandmothers, so the title “Victorian Grandmothers” refers also

to two great-grandmothers, and because we have information about her, one

great-great-grandmother. All these women

were born, or lived most of their lives, in

SARAH JENKYNS - MY FATHER’S GREAT GRANDMOTHER

IMPORTANT DATES IN THE LIFE OF SARAH JENKYNS

Her father was

Reverend J Jenkyns, vicar of Evercreech in

She was born in

1790

Her elder

sister married Dr Thomas Gaisford, Dean of Christ Church.

She was the

second daughter.

One brother,

Richard, was Master of Balliol and Dean of Wells.

Another

brother was Fellow of Oriel, Canon of Durham and Professor of Divinity at

She married

John Gale Dalton Thring (born 1784) on 1st October 1811 at

Evercreech Somerset

Their children

were:

Theresa born

18th July 1815

Theodore born

August 1816

Henry born

November 1818

Edward born

1821

Godfrey born

25th March 1823

John Charles

born 11th June 1824

She died on 16th

September 1891

SARAH’S

OBITUARY

This is the

only one of my eight great great grandmothers about whose lives I have any

information. Amazingly this obituary

from the Mother’s Union Journal of January 1892 survives. I don’t know Sarah’s relationship to the

author. Her brother Richard was a

reverend gentleman and master of an Oxford college so was probably not allowed

to marry by his college; her other brother may have had children when he went

from being a fellow of Oriel College Oxford to Durham University, where the

dons were allowed to marry. The obituary

may have been written by one of his descendants.

A REMARKABLE MOTHER

M. S. Jenkyns

Last

September the death took place of Sarah Thring, aged 101

years, widow of Rev. John Gale Thring, rector and squire of Alford,

She was the

second daughter of the Rev. J Jenkyns, vicar of Evercreech. Her brother, Rev. Dr R Jenkyns, was Master of

Balliol and Dean of Wells, and another brother, Rev. Dr H Jenkyns, was Fellow

of Oriel, Canon of

Mrs

Thring’s sons were no less distinguished than her brothers. Edward, the beloved late headmaster of

Uppingham School, made that celebrated school what it is; Henry, now Lord

Thring, was a distinguished Parliamentary Counsel of the Government, and his

mother lived to see

him made a KCB and a peer; Godfrey, prebendary of Wells and rector of

Hornblotton, is the author of many well-known hymns, among them “Saviour,

blessed Saviour,” and “Fierce rage the tempest o’er the deep,” and he also

compiled “The Church of England Hymnbook”.

With him his mother lived at Hornblotton since the death of her husband,

who lived to the age of ninety[1].

Her eldest

son, Theodore, was a county magistrate for

It was a

most touching sight to see the two graves side by side, lined with moss and

flowers, and the two coffins quite covered with beautiful wreaths, and the

three surviving sons with their grey hair, looking like a past generation

themselves. Out of her twenty-nine

grandchildren twelve

were present, five of whom were Theodore’s sons, and, with another grandson,

carried their father to the grave.

It is

remarkable that Mrs Thring spent her whole life almost in one spot: her

childhood at Evercreech, her married life at Alford, and her widowhood at

Hornblotton, all within five miles of each other. Her long life was one of usefulness and

happiness, the greater part of it being spent at Alford.

She

travelled very little, and rather despised “change of air;” but that did not

prevent her from taking a keen interest in all that was going on in the

world. Perhaps the most remarkable

traits in her character, retained to the last, were her meekness under

provocation, her intense sympathy with the suffering of distressed in mind or

body, and her very strong sense of duty.

If she saw it was her duty to do or bear anything, it never occurred to

her whether it was agreeable or not; it was done, or borne, as a matter of

course.

Up to the

age of ninety-three she was in good health, and though since then she was a

complete invalid, her strong constitution was shown by her surviving five

paralytic strokes (the last of which deprived her of speech) and several bad

illnesses, such as congestion of the lungs, bronchitis, etc. Those who nursed

her during those last years were attached to her, so that it was a pleasure to

do anything for her. She seemed to be a

mother to them all, and was so good and patient, besides being cheerful and

full of fun.

This

cheerfulness was a matter of principal with her. She said once, “I have tried all my life to

be cheerful, and now I am reaping the benefit”.

There were no dismal, long faces in her room. It was the centre of interest in the house,

and she enjoyed hearing what went on in the outside world. The Hornblotton choir will never forget how

she liked them to come up to her room and sing the Christmas carols, and how

she shook hands with them all afterwards.

She has

left a blank that can never be filled; but for her own sake we can rejoice that

after waiting so long she has gone home to the “rest that remaineth for the

people of God”.

SARAH’S BROTHER RICHARD JENKYNS

Richard

Jenkyns was master of Balliol College Oxford from 1819 to 1854. Benjamin Jowett, his successor as master,

described Richard in 1888 as “short of stature and very neat in his

appearance; the deficiency of height was more than compensated by a superfluity

of magisterial or ecclesiastical dignity.

He was much respected, and his great services to the College have always

been acknowledged”. He was

apparently no great scholar but he was a shrewd organizer and good judge of men

and had an inflexible view of what was right.

In his last years as Master he instituted an ambitious rebuilding

programme and his obituary in the Times said that “He found Balliol a close

college among the least distinguished collegiate bodies at

SARAH’S

CHARACTER

The obituary

makes Sarah sound almost too good to be true; however there is other evidence

concerning her character. In a book

about the life of Sarah’s third son, Edward Thring[3],

Parkin describes the family background of the young Edward (and therefore of

the other siblings). He also touches on

the characters of their mother, Sarah Jenkyns, and their father John Gale

Dalton Thring. Parkin tells us that one

of her sons said that: “Mother’s

idea, too, was that everything should be sacrificed to work and duty” Parkin goes on: “He [i.e. Edward] never

spoke of his mother without a tender dropping of his voice, which made one feel

that all that sweetness and tender sympathy which was so marked a

characteristic of him was an inheritance from her’”.

Later Parkin

says: “Once when asked for recollections of Edward’s earliest years, his

mother said that he ‘never seemed so happy as when he was lying on his face on

the floor reading’. A neighbour used to

relate that, making a call one day at Alford, she discovered the lad, then six

or seven years old, thus disposed in the library, and completely absorbed in a

huge volume of Indian history. The

visitor remarked to Mrs. Thring that it seemed a mistake to let the boy read a

book so much beyond his years. The

mother’s reply was that no book which awakened such deep interest could be

considered beyond a child’s years.” Sarah’s

reply to her visitor’s criticism seems wonderfully broad-minded for Victorian

times. There have been avid “bookworms” in later generations of the family as

well, including me.

Parkin

concludes “Those who knew her in middle life remember in her a rare

combination of mental activity and of Christian character at once gentle and

firm. To those who saw her in her later

years she presented a wonderful picture of a happy and interesting old

age. Till long past ninety she retained

her faculties almost unimpaired; her hand-writing was as firm and clear as in

middle age; her memory keen and retentive; her literary interest scarcely

diminished.” Even when one has

discounted the Victorian sentimentality and high moral tone she still sounds a

remarkably pleasant, interesting and sensible woman.

Another book about Edward Thring[4]

is mostly a summary of the information contained in Parkin, however some of the

paragraph concerning Sarah is worth quoting:

“No biography

of Mrs Thring has been written and we only know of her from the tributes of her

friends and her children, but the picture which these give is one of

extraordinary charm. To begin with, she

was a woman of strong mental power with a clear, penetrating mind and a sense

of duty as definite as her husband’s but with a gaiety and humour in addition

which he does not seem to have possessed.

This gaiety and sense of fun she shared to the full with her children,

entering deeply into the joys and adventures of their second world (i.e. their outdoor

life) and reinforcing

them, by the strength of her character, in their struggles with the first (i.e. their

relationship with their father). She gave them, moreover, the

deepest and tenderest parental love without the least trace of spoiling or

softness – a combination, one may guess, as rare in those days as it is in

these. Finally, she was deeply and

serenely religious. Had the boys’ notion

of religion been taken solely from the example of their father, worthy man as

he was, they might well have dismissed it when they grew older as something

detached from real life, but their mother made it quite impossible for them to

take any such view. For their father they felt affection and respect, mingled

with fear, but their mother they adored…”

JOHN GALE DALTON THRING

According to the family tree drawn up by a Thring in Victorian times

John Gale Dalton, Sarah’s husband, had one sister but no other siblings. A note on the tree has some interesting facts

about his parents:

“On Tuesday

morning August 24th 1782, was married at St Edmund’s church

Parkin[5]

has observations concerning the character of John Gale Dalton Thring: “But the respective influences of father

and mother were in strong contrast. It

was said by a keen and competent observer of men who knew John Gale Dalton

Thring intimately, that he applied to the small details of family and parish

government, abilities which might have made him a great statesman or a great

general. His own early desire had been

to enter the army, but he took orders in deference to the strong wish of his

mother. The duties thus assumed were

not, perhaps entirely congenial to him, but they were discharged with

conscientious care and fidelity”. I guess that

as he was her only son

“The parish

was small, however, and the work light, leaving time for other things. He was a magistrate for the county as well as

rector of the parish. He managed his own

considerable estate. He had the fondness

of English country gentlemen for outdoor life, and was known as the best and

boldest rider in the

Winchester

School, where he received his early training, and St. John’s College,

Cambridge, where he was at the head of one “side[6]”,

when Lord Palmerston was at the head of the other, had made him a sound and

polished scholar. His two elder sons

received from him the whole of their preliminary training for Eton and

John Gale Dalton Thring (date

unknown)

If his

teaching was sound his rule was rigid.

He was a man of strong and unbending will, and none had better reason to

know this than his own family. His

domestic government was not merely strict – it was autocratic and

exacting.

‘The fact

that the Thrings as boys and young men did not revolt against their father’s

arbitrary interference with the details of their daily life always seemed to me

a striking proof of the depth and sincerity of their Christianity’, was said by

an intimate friend and relative who saw much of the home life at Alford in the

early days. ‘Just, but hard’ is the

description given by another”.

Parkin[7]

quotes an entry from Edward Thring’s diary dated December 14th 1874.

It reads thus:

“A solemn

epoch. My dear old father passed away on

Friday last, December 11th.

My dear old father, how thankful I am to have had a brave good man as my

father according to his lights! I thank

God for him. And my dear, dear mother –

O may God keep her and comfort her; sixty-three years married, and for the last

fourteen or fifteen all her daily work and thoughts centred on him, and he is

gone. But a more saintly woman in

practice and faith I believe cannot be found.

God does and will support her with His holy comfort”. I wonder if there is any veiled meaning behind

“according to his lights”. By all

accounts, including his own, Edward had a fairly miserable time when he was

sent away to a very unpleasant boarding school at a young age, and Parkin makes

John Gale Dalton Thring sound like a bully.

I can’t help thinking that although she lived in great comfort Sarah

must have had a somewhat tempestuous life, with an autocratic husband and five

robust sons. Interestingly I have seen

no mention in Parkin of the two daughters listed on the family tree, Theresa

and Elizabeth. Neither died young. Theresa married Augustus Fitzgerald and lived

to the age of 52 and Elizabeth, who was unmarried, lived to the age of 40. Possibly Parkin discounted them as being of

too little interest to mention.

ALFORD HOUSE

Alford House,

where Sarah and John Gale Dalton Thring brought up their five sons and two

daughters, is in a small village 2 miles west of Castle Cary in

Parkin

mentions life in the village:

“The village

contained only a small farming population, and in the life at Alford there was

something of that isolation which not unfrequently makes for individuality of

character in those brought up subject to its influences. But as the five brothers of the family were

not widely separated in age, there was within the home itself abundant material

for a cheerful boy life”.

“Other

companionship was not entirely wanting.

The most intimate holiday playmates of the boys were their cousins of

the Hobhouse family, whose seat, Hadspen, is but a few miles distant from

Alford. The relations between the two

families seem to have been particularly affectionate and intimate. One of the Hadspen family remarks in a note:

“I have always reckoned on all Thrings as steadily as brothers, and I never

found them fail yet.”

THE LIVES AND CAREERS OF SARAH’S CHILDREN

THERESA married Archdeacon Fitzgerald and had 2 daughters and 2 sons.

THEODORE took over from his father as squire and was also a county

magistrate for

HENRY

A version of

Henry’s career was published in conjunction with a cartoon by ‘Spy’ in Vanity

Fair on June 29th 1893. It is

entitled “Statesmen Number 615 Lord Thring” and I wonder what he thought of it

when he read that he had been “warped into detailed narrowness”.

“He is the second of five sons born to the late Reverend John Gale

Dalton Thring, of Alford House in Somerset; of whom three became parsons, one

Edward, now dead, was the excellent and popular headmaster of Uppingham school,

and himself, Henry, after being grounded at Shrewsbury School, went to Magdalen

College Cambridge, got third place in the classical Tripos and became

fourteenth Junior Optime and a fellow of his college. Having achieved so much and being still most

industriously inclined he went to the bar with qualities and luck that together

some three-and thirty years ago improved him into Counsel to the Home

Office. Eight years later he rose to be

Parliamentary Counsel; after which, as a matter of course, he was honoured with

a KCB, and on retiring from Office seven years back, he was very naturally

offered a peerage, which he accepted as a slight part of the reward to which

his years of service had entitled him from a grateful country.

He has now lived through three quarters of a century; but he found

himself in the House of Lords too late to cut the figure that he might there

have cut as a younger man. For he had

been warped into detailed narrowness by a long life of drudgery spent in the

unwholesome drafting of parliamentary documents such as would have made musty

the talents of a better man. Yet has he

written much outside the routine work of his Office. Among other Bills he drafted the Joint Stock

Companies Acts of 1856, 1857, and 1858, the Joint Stock Banking Companies Act f

1857, and the consolidation of those acts by the Companies Act of 1862; whereby

he became, as he thought, qualified to contrive that work on ”the law and

practice of Joint Stock and Other Companies,” which still, ‘though much edited,

bears his name; in which he explained to those concerned how the principle of

Limited Liability was meant to work. He has also written on the Succession Duty

Act, and on “Practical Open Legislation”; of the clerical parts of which at

least he should know as much as any man.

He lives at Egham and he is a

I found another reference to Henry’s work when searching the

Internet. In 1851 a pamphlet was

published entitled The Supremacy of Great Britain Not Inconsistent with

Self-Government for the Colonies. The

explanation accompanying this entry reads: “Published on behalf of the

Society for the Reform of Colonial Government, this pamphlet discusses the

Colonial Bill proposed by Sir William Molesworth. Thring was the Parliament Counsel. Considered one of Parliament’s greatest

legislative draftsmen, he had a formidable knowledge of English law and

government. He was the author of many

books and articles of law and procedure.

Many of these, such as his treatises on military law, were important

works that went through several editions.”

Three letters Henry Thring wrote to his niece Nona Thring, one of John

Charles’ daughters, have survived. Nona

went to Newnham College Cambridge to read mathematics in 1891 so the first two

must have been written when she was still at school. The story of her life as

far as I know it is in the section about her mother, Lydia Meredith. The letters are all on beautiful paper with a

very fancy embossed red coronet above a capital T. They read as follows:

January 19th

1889

5 Queen’s

Gate Gardens S W

Dear Nona

I have

heard with the greatest satisfaction of your success in your examinations- it

shows how steadily and ably you have availed yourself of the opportunities of

learning afforded to you. The greatest

pleasure I think I ever experienced was the receipt of the news that I had

taken a good degree at

Your

affectionate old Uncle

Thring

Tell your

father that I thank him for his letter and will answer it (illegible)

August 12th

1890

Alderhurst,

Englefield Green,

Dear Nona

We are

extremely pleased to hear of your great success in your examinations. It shows not only that you are possessed of

the requisite ability to get on in the world but what in my judgement is of

still more consequence, of energy, perseverance and force of character – The

greatest pleasure I have ever felt in life was the satisfaction of (illegible)

a high degree at Cambridge. I began then

to feel that I should be able to stand upright on my own legs and make my way

for myself – I have little doubt that you think now much as I did then. No

doubt you like me will have a sharp struggle and many disappointments but

perseverance overcomes everything – and I have little doubt that should life

and strength be given to you – you will be a successful and what is still

better a useful good woman.

Your

affectionate Uncle

Thring

June 12th

1895

Alderhurst,

Englefield Green, Surrey

Dear Nona

Of all the

honours I have gained in life the one that gave me the greatest pleasure was

the attainment of a first class in the Classical Tripos in the year 1841. It came at the opening of my career and

seemed to spur me that if I worked hard I might consider that I had ability

enough to do what any other man might reasonably expect to achieve. You may imagine then how heartily I

congratulate you on your success in becoming a wrangler – You have broken the

spell which appeared to hang over our family none of whom except yourself have

shown any aptitude for mathematics and I hope and believe that should God grant

you health you have a just expectation of a happy and successful life – It is

pleasant to think how many doors are now open to a woman in ?literature,

teaching in colleges and other vocations which were entirely closed to her when

I was young so that a University Honour is not only a great distinction but a

substantial benefit – That you may be good successful and happy is the earnest

wish of your affectionate Uncle

Thring

I can’t help

thinking naughtily that these letters make Henry sound somewhat pompous. The reference to being a “useful and good

woman” in the second letter is very interesting. I have read that the Victorians put

“goodness” as a quality in a person’s character very much higher than

“cleverness” – and particularly for a woman. To give Henry credit he does seem

to be genuinely pleased with, and proud of, her success. I like the reference to the family

non-aptitude for mathematics, which luckily didn’t seem to hold true for

subsequent generations of Thrings.

Henry had two

daughters. I can remember being taken to

have tea with one of them in a grand and gloomy

EDWARD was

educated at Eton and in later life wrote to his brother Godfrey that “The

grind of the schooldays at Eton had much in them that was exceedingly

repressive, and whilst I give unabated thanks for the power of working against

odds that my early training gave me, I lost a freshness and spring of

imagination that has never come back”.

In addition to

Parkin’s Life and Letters of Edward Thring I have a memoir[8]

of Edward written by a former pupil, and subsequently a teacher at Uppingham,

who therefore knew Edward from two perspectives. His initial inscription reads: “I dedicate

this memory of our master to those many who praise in silence him who taught

them the worth of life”.

Chapter IV is

entitled “The Hero as Schoolmaster” with subheadings “The Man – The Leader –The

Hero”. In 16 extra-ordinarily flowery

Victorian–style pages he gives us an insight into Edward as a man. They can be summarised as follows: Edward was genial and humorous but “altogether,

in his sociality there was too much force for general pleasantness”; I’m

not sure I like the sound of this! He

was short and stocky. He had been an athlete and was “always in hard

fighting condition”. He excelled at fives, and was still playing in his

fifties, and was also keen on playing football and cricket. He was extremely

energetic - “energy seemed to us the very soul of him”. When he spoke to the

boys he inspired them and they “believed him to be a hero”. “He treated

everything as if it mattered supremely”.

“He appeared to have a genius for being unworldly”. “Last, at least in my memories of these times,

he invented a smoke–consuming fire-grate, patented it and warmed his study with

it: an earthenware eggshell of a thing, swinging on a pivot”. This is a fascinating detail because my

father, his great nephew, also invented and patented a smoke-consuming fire-grate,

probably with as little success. Skrine

concludes by describing Edward giving a sermon “with rarely a movement

except to turn the leaves; there was only the firm-outlined figure, energetic

in stillness; the voice charged with steady passion, the eye which wonderfully

took fire with the voice, and without grace of feature, lit up the stern face

into beauty: only a man of faith, speaking of things he knew.”

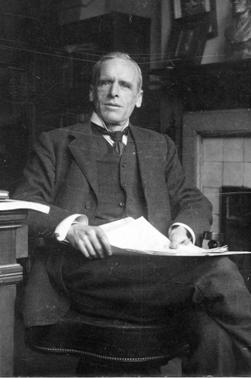

Photograph of Edward Thring from his “Life and

Letters”

An oft-quoted

Victorian maxim is “spare the rod and spoil the child” and all public school

headmasters at this time were “floggers”.

Another book[9],

quotes the following story:

“…He

discovered a proposed game posted on the boards as: THOSE WHO HAVE BEEN FLOGGED

BY MR THRING V. THOSE WHO HAVE NOT.

‘Ha!’ he said, as he ran his pencil down the list, ‘if that game takes

place, all the players will be on the same side’.” However Skrine approves of his methods of discipline and says: “it

was only a miserable percentage of them who had a first-hand experience of the

beneficent whip. Its exercise was

guarded too by strict limitations”.

The author tells us that flogging was administered only by the

headmaster and in public and also that “his laws were few; they were easy to

keep; and there were plenty of things to do which were more amusing than

breaking them”. In fact “there

was room for all of us on our playing grounds, and the games were organized to

include everyone, and not only the cricket or football worthies”. Edward

also introduced carpentry and music lessons. The author states, “Another most

powerful instrument of discipline was the extension through the school of

self-government “. “What Thring did of

his own was to make not the sixth form responsible for the society, but the whole

society responsible for itself”. One final quote from this memoir on

discipline: “but if his severity and justice made discipline inevitable, it

was another quality which commended it to us.

Among the secret springs of discipline was his tenderness”.

Edward Thring

wrote and published many books including the Theory and Practice of Teaching

and Sermons preached at

Edward Thring

died suddenly at the age of 66 while still working as head master. While building up the school he had had many

worries concerning debt, which may have taken their toll on his health. He had

2 sons and 3 daughters.

Family legend

passed down to us by our Great Uncle Ernie, who was Sarah’s youngest grandchild,

told us that one of Edward’s sons married a bar maid and that Edward never

talked to him again. How true this is I

do not know but it certainly seems very Victorian.

GODFREY

Godfrey was

educated at

Godfrey was

first his father’s curate and later became rector. He resided in the vicarage at Hornblotton,

which his father had built for him in 1867.

He finally married at the age of 47 and he and his wife supervised the

building of a simple and beautiful new church at Hornblotton. His bride was

aged 38 and they had only one child, a son.

Godfrey was a

prolific hymn writer and also edited published collections of hymns. When I started primary school we used a

hymnbook, which contained several hymns by Godfrey Thring, and I used to feel a

great sense of family pride whenever I saw his name. Godfrey was also an inventor and very forward

thinking. He influenced his father to

have a hydroelectric generator installed

at Alford using the water of the local river. Later a paraffin engine was added to provide

electricity when the water flow was low.

He installed the “first electric turret clock in the kingdom made

with a striking apparatus” in the new Hornblotton church. He invented a stile for walkers, which was

easy to negotiate, could not be left open, and was proof against cattle and

sheep.

He retired in

1893 at the age of 70 and died in 1903.

As for JOHN

CHARLES, Sarah’s youngest child, his story is in the section concerning Lydia

Meredith.

IMPORTANT DATES IN THE LIFE OF

Her mother was

Lydia Eliza Dyer born 1796

Her father was

Samuel Meredith born 5th August 1794

Their marriage

date is not known

Her older

sister was Mary de Saumary Meredith born May 21st 1826

She was born 4th

August 1830

She married

John Charles Thring (born 1824) on 18th May 1858

Their children

were:[11]

Lydia Marian

Ethel born April 18th 1859 at Uppingham

Godmothers:

Mary Meredith, Eliza Marian Thring. Godfathers: Edward Thring, Hugh Dyer.

Charles Henry

Meredith born January 21st 1861 Uppingham

Godmothers:

Lucy Merryman, Mary D S Meredith.

Godfathers Henry Thring, Charles Hoskins

Lionel Charles Reginald born September 5th

1862 Uppingham

Godfathers:

Godfrey Thring, John Baverstock

Godmother:

Anna Eliot

On the 4th

December 1863 - a boy stillborn (from a fall)

Gertrude

Godfather:

John Medland Dyer

Godmothers:

Mabel Sarah Fitzgerald, Mary Bell

Llewellyn Charles Waldron born July 11th

1866 at the Chantry Bradford on

Godfathers

Henry Stilwell, Andrew B...........

Star........ Godmother: Mary

Agnes Roche

Theresa Anne

Lydia born November 22nd 1867 at the Chantry

Godmothers:

Constance Starky, Clara Wayte. Godfather

Thomas Guy Barlow

Amy Gwendoline

Mary

Godmothers:

Caroline Crabbe, Laura Roche. Godfather:

Theodore Thring.

Nona Alice

Godmothers:

Walter Hugh

Charles Samuel Born May 30th 1873 The Chantry

Godmother

Ellen Whinfield Godfathers: Francis

Baldwin Leighton, Francis H Du Boulay.

Ernest Walsham Charles born Feb 22nd

1875 The Chantry

Godmothers:

Arabella Dyer, Ella Jane Robinson. Godfathers: Ernest A Fuller, Wm. Walsham How.

In 1920

The life

must have been rough. I have heard him

say that as a middy[14],

his dinner table was often an upturned bucket.

He must have made himself liked by the men, as he told me once, that on

first going ashore to India, an old sailor said to him ‘if you wants some

money, Master Sam, I’ve got some in old stockings and I don’t want it; you can

have it’. There had been much prize

money taken by the ship’s crew, and some of the crew of the Captain’s gig had

pierced guineas as buttons on their jackets.

It was five years before my father came back to England.”

Lydia

Meredith’s mother, who was Lydia Dyer before she married Samuel, was the “eldest

daughter by the second wife of John S. Dyer, Chief Clerk (as it was then

called) of the Admiralty

It is

hideously confusing to have mother and daughter

When Lydia

Dyer married Samuel Meredith, Samuel “was a lieutenant in the RN attached to

the

When command

of the Vigilant ended Samuel asked for a shore appointment. He was “given the command of the

As an infant

The

While they

were at Chicklade Samuel was appointed Inspecting Commander of the Swanage

Coast Guard District in

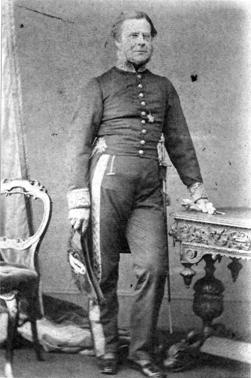

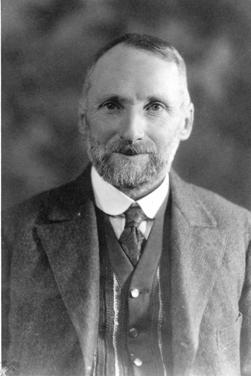

Captain Samuel Meredith R N –

Soon after

they arrived at Swanage, when Lydia must have been aged five, her father’s

armed mounted guard called Heath, who was a friend of hers, put her up into the

saddle of his thoroughbred mare Betsy, where she “sat astride, holding onto

his holster pistols. Betsy suddenly

broke into a gallop and went up onto the down above Durleston Head. I enjoyed my scamper exceedingly, but my

father mounted his horse, headed Betsy and soon caught her. I was ignominiously lifted off and sent to

the schoolroom for the day”. Later

in the memoir she says “my sister did not care much for riding, but I was

devoted to it, and my father often let me ride with him, when he rode to some

of his stations. I was then 7 years old,

and my father was very much pleased with the way in which I rode Jack”. She tells of riding with her father on a

dangerous path on a great slope, which ended in a steep cliff. It sounds as if her father greatly enjoyed

the company of his feisty little daughter.

The “plucky

governess” was called Miss Swain and “was a good botanist. When taking us out for walks she used to

interest us so much in the flowers that I have been grateful to her ever

after. Our pony, Jack, went with us on our

walks so that either of us could ride when tired, and I remember on one

occasion Jack bit out the whole crown of Miss Swain’s straw bonnet as she

walked in front of him”.

The

description of life in Swanage ends with the following: “My father’s strict

rule had great effect in capturing many of the smuggling ‘ventures’ of the

Swanage people, and before he left, smuggling had greatly diminished on that

coast”.

When Samuel’s

Swanage appointment ended the family moved to the Old Rectory in Boyton,

Wiltshire.

EARLY LETTERS

TO

By good

fortune I discovered a cache of 31 letters that must have been preserved by

Mary. Four of the letters are written by

The

season of Christmas is now fast approaching, what a solemn event it is to

commemorate the birth of our blessed saviour, and when we consider the amazing

love of God in giving his only son to

suffer and die for us it ought to fill us with love and gratitude to him.

You told me

in your letter that you were collecting shells and fossils, which must be very

amusing to you. I dare say your

governess is kind enough to explain them to you and tell you their names;

should I have the pleasure of seeing you at some future time, I should very

much like to see them.

You I doubt

not are as fond of the study of history as I am. I have lately finished that of Rome, which I

consider very entertaining and am about to commence the History of Greece which

I hope to be as much interested in; our wish however ought not to be merely to

read for amusement, but that we may derive benefit and instruction, and

endeavour to retain it.

Papa and

Mamma unite with me in kind remembrance to your dear parents and your

sister. I shall be always pleased to

hear from you when you have leisure.

Will you

please to present my love to Miss Swain and believe me to remain your

affectionate young friend, Frances Elizabeth Frowd”.

Considering

that Mary Meredith was aged ten, and guessing that

The next

letter was written by Lydia Dyer on August 13th 1839. Mary was staying with friends in Hindon,

Wiltshire, and Lydia Dyer, Lydia Meredith and Samuel had gone to stay in

Limmington near Ilchester with William Dyer (Lydia Dyer’s brother) and their

sister Ann who kept house for him.

William was a curate and Lydia Dyer mentions him often in the letters.

“My dearest

Mary

I am

anxious to fulfil my promise of writing you, because I know you will be

anticipating the pleasure of a line from me.

We arrived at this place on Saturday in time for dinner at five o’clock

and found dear Uncle and Aunt quite well.

Sunday was a very happy day with us all, and to none more than Lydia;

she often, very often, thought and spoke of you and felt pleased in the

reflection that you were also enjoying a similar treat with herself.

Yesterday we

spent the evening with Mrs Williams.

There

SAMUEL MEREDITH’S APPOINTMENT AS CHIEF CONSTABLE OF WILTSHIRE.

According to

Miss Swain, the “dear

governess”,

left them in late 1840 or early 1841 to take charge of an old relative, and

LETTERS TO

The letters give a good idea of the kind of life that

It is obvious from the letters that Samuel called in to see Mary frequently

whenever he was in

This is from the first letter sent to Mary after she went away:

“Behind my

dressing glass, I found these words written on the wall “ dear Mamma I shall

never forget you”. I instantly

recognized my Mary’s writing and by that the workings of her heart. May the constant remembrances of your Mother

lead you to remember “Him” who has spared her to you and believe me dearest

love any blessing you find in her must be traced to God’s love for you in thus

smoothing your pilgrim path through life.

We all

think of you, talk of you, and love to hear from you.

You do not

mention Elizabeth [one

of the servants] in your note, but as I am sure it was a “forget” (which by

the bye, is an excuse I do not patronize) I have substituted a remembrance to

her, as no one in the house thinks of you more than she does.

I dare say

you feel the cold very much, we all do, especially poor Mamma, but I am

thankful to say I am quite as well as when you left me. Doubtless you miss your fire in the evening,

but my Mary is quite equal to any sacrifice of feeling where duty appeals to

her and others are cheerfully complying with circumstances. These little privations must be looked upon

as the [???] in the

weight of pleasure in the society of so many young friends. When next you write you must give me an

account of your daily arrangements. Your

Governesses, schoolfellows, nothing is too trivial connected with my darling’s

welfare to give pleasure to her fond parents.

God bless you my beloved child.

Papa sends his affectionate love”.

The following are examples of some of the recurring themes from

different letters; the first four show Lydia Dyer’s pre-occupation with health

or the lack of it:

“I was a

little anxious upon first reading your note, as any thing like spontaneous

palpitation of the heart, is quite foreign to your constitution, but upon

reflection, I anticipate, that the cause has originated in your need of your

aperient[22]

medicine which I hope you have received by this time, and have resorted to its

salutary aid. Should Mrs Boscawen still

think you had better have the “Fluid Magnesia” I shall be obliged to her to

send to Quareys for a shilling bottle of it for your use, as Mrs Seagram

assures me its qualities are much deteriorated after the cork has been

withdrawn; therefore it will be better to have but a small quantity at a time;

by promptly replacing the cork that quantity will be available while it is

good.”

“ I should

like you to purchase a cake of camphor soap and use it to prevent chilblains,

but you must take care to keep it carefully wrapped up in the lead paper in

which you buy it. Or perhaps it would come lighter to your purse to have two,

or three ounces[?]

of camphorated spirit and when your hands are dried out of the water after

washing them rub them well with the spirit and let it dry in.”

“I am a

close prisoner to the house, but thank God in very much better health than is

usual with me at this season of the year.

I am urged, by no means to venture out, and if that precaution will help

to preserve my health to enjoy the companionship of my dear girls, I am well

repaid.”

“…….although

on my return to Boyton I am reminded continually of the temporary loss of one,

who is loved, valued, and missed very much.

[Presumably she

is referring to Mary away at school.] Still

we are expecting gain from our loss, and that seems to qualify everything: your

affectionate sympathy in all my weaknesses, is always gratifying; but I

wish them to have only their just weight, remember my love, so sensitive a

frame as mine, is more susceptible than is to be desired and therefore

needs the utmost endeavour to suppress its morbid effects.” (The underlining is mine).

This next

extract makes me fell quite worried about their care of the dormice. “You will think of me I doubt not; dear

Papa left us yesterday for a long tour, and will not return until tomorrow

night. I think he is likely to see you

on Thursday or Friday. I will talk to

him about

The next three

extracts are an insight into Lydia Dyer’s attitude to her daughters:

“Your

letters are every way cheering to me, because they manifest such a very amiable

spirit. Humility is a cardinal Christian

grace, the very touchstone of sincerity in our desires to “learn to do

well”. The only one which elevates us in

proportion, as we can surrender self and selfish principles”, [etc etc for many more lines]

“Lydia has

written you a note which served to gratify her – but I do not think it is fit

to shew, therefore destroy it when you have an opportunity.”

“ I am

afraid I shall not be enabled to dispatch the shoes as I had intended by post

tonight as I have been sadly hindered by a great difficulty I found in getting

any ribbon to match the pale blue silk, but I have at length succeeded pretty

well and if I have no other means of sending them tomorrow shall hope to

enclose them in an envelope and send them by post – in that case they will

arrive on Sunday morning which I shall regret but as there will not be one line

with them you must content yourself with waiting until Monday morning before

they are opened, as I am truly sorry they should interfere in the slightest

degree with your Sabbath duties. Let me

hope you will explain the circumstances under which it so happens”.

Being told

exactly when to open a parcel sounds a bit like “control freakery” to me, but

also goes to show how very seriously Lydia Dyer took her religious duties.

This extract

concerns their servants: “Bright is going to leave us, for his habits have

recently become very loose and idle.

There is a most respectable man coming as groom, who will live at the

cottage and act as porter at the gate. I

am sorry, and disappointed at Bright, but am really not sorry to lose him under

such circumstances. Sarah and Ellen are

quite well and going on extremely well.

I have at present a work-woman living in the house from Dr Daws, where

she is in almost constant work, but Mrs D has kindly spared her to come and

make up curtains, carpets, and different things which our new house

requires.”

.

There is one passage about Mary’s education that I find interesting: “You allude most sweetly to the

little deficiency in French and Music and will I am sure see the propriety of

doing all you can, in a private way, to perfect yourself in both. Mrs Boscawen most kindly and tenderly tells

me of it, as a regret, that you can not commence another language until you are

more familiar with French; and the ground work of music is not well understood

by you. Will

One letter discusses a stay at

the school in

“I am quite

delighted to find that you enjoyed dear Lydia’s visit so much, your feelings on

parting with her, were nature’s own, such not to be regretted, but improved to

the mellowing of your character: may all these little trials have that

tendency, and thus fit you for that genuine test of true Christian virtue, “To

weep with those who weep” and the greater grace “To rejoice with those who do

rejoice”, neither of which could we do, unless there was a kindred chord in our

own bosoms, that could feel the “grief” of the “joys” which claimed our

sympathy. Our reason tells us that could

we take a birds-eye view of all the sorrows human nature displays, at one

glance, we should soon feel how insignificant our little trials were in

comparison; and yet how soothing, how animating, how cheering, to know, and

feel, that when the heart is oppressed, there is no occurrence too trivial for

God’s sympathy, that we can conscientiously carry to Him.

I am quite

pleased at the account you give of dear

Two letters

refer to plans for

“I write

you a hasty line to tell you that Papa will certainly see you tomorrow (DV[23])

but not until about 1, or 2 o’clock and will not I fear be enabled to remain

long with you.

Dear

And later

after they had moved from Boyton House to Easterton House:

“There is

one disappointment I am anxious to do every thing in my power to soften down to

you, which is the necessity for our deferring

The other item

of note is the appointment of William Dyer (

While staying

with William in Imber Lydia Dyer wrote to Mary as follows:

“It has

been thought good for me to have a little change of air, and scene; and as your

dear uncle’s Christian society is always soothing and refreshing to me, I have

selected his manse as the most congenial to my wishes and quite as long a journey

as I can comfortably bear [NB

6 miles]. It is apparently, a great delight to him, that such a plan should

have been fixed upon, and I am looking forward to the enjoyment of a spiritual

feast tomorrow in the midst of

The village

is all upon the qui vive at our sojourn: and having visited several sick-poor,

and enjoyed the blessedness of a visit to the house of mourning there is a

general muster of all the invalids in the place to wish their claim upon us for

a visit. I have seen several today, but

as I am glad of a stronger arm than my own to lean upon, I feel the propriety

of submitting to the opinion

of my friends as to the prudence of maintaining a system of quiet and repose

and therefore cannot hope to see them all, they are however to assemble in the

School room where we may all unite in holy communion and take sweet council

together”.

There must

have been a bereavement in the family as the above letter and all following for

the next 3 months are written on black edged paper. At the end of the visit to Imber Uncle

William went back to Boyton with them and later Lydia Dyer wrote this:

Uncle

William leaves us for Imber this afternoon, for tomorrow’s sacred duties, and

returns here on Monday morning. Eliza [William’s house

maid] will remain here

during his absence. I very much enjoyed

the opportunity of passing a Sabbath with him.

The whole observance of the day was so primitive, so simple, and so very

sweet, it really appeared, a shadow, of heavenly enjoyment. Dear Uncle (in his native ingenuity) has

repaired all the flutes and instruments which appear to have been useless for

some years, and certainly he had in the easiest and simplest manner secured the

most perfect harmony throughout the congregation. So painfully sad had been the sectarian

spirit of this little community that the churchwardens assured me not more than

12 persons used to frequent the church at all, but it was truly gratifying to

me to witness the mass who were congregated in their most venerable edifice,

and during the sermon several old people stepped “softly” to the foot of the

pulpit stairs with the intense anxiety to catch every word that fell. May your dear uncle (who appears as a

stripling among a hoary-headed flock) be instrumental in imparting that peace

which passeth all understanding instead of that false peace in which too many

appear to have [illegible]

themselves.

On leaving

Imber on Monday last it was as amusing as it was interesting to watch the

proceedings at the parsonage. The house

was to be shut up, and left in charge of the schoolmistress, and it became a

consideration to dispose of all perishable articles. A clandestine peep into the movements of

“mine host” discovered him with upturned cuffs, dividing a cold lump of beef

and quarter of lamb into platefuls, and as the motley group of messengers stood

by, they were charged thus “this is for the clerk’s wife”, “this for the tall woman the clerks wife’s friend”,

“this is for poor Jacob Meaden the sick thatcher”, “this for the dumb man”,

“this for the sick man who is dying”, “and this little pudding for poor old

Bartlett”, “the seed cake to be taken to the school and divided amongst the

children”. William had been rector

for such a short time that he did not yet know their names!

The last of

the letters from Lydia Dyer is dated Feb 19th 1842 when Mary must have

been nearly 14. It looks as if any

subsequent letters have not been preserved.

It is possible that

LETTERS FROM

Mostly the

five letters from

My very

dear sister Mary

I am very

much obliged to you for the threads of wool you so kindly sent me by dear

Papa. Last Monday one of the poor little

children at

In the

Mr Roche

came yesterday and remained till this morning: he says he has his brother’s

collection of coins and will send them to us the first opportunity.

I enclose

you the account of the Royal Christening[25]. She is your namesake and had 6 godfathers and

godmothers. Hoping you will like it I

remain my dear sister Mary your affectionate sister

SAMUEL’S ROLE

AS CHIEF CONSTABLE

Throughout the

time-span of the letters Samuel was

setting up the Wiltshire County Constabulary.[26] At work he was apparently a fairly remote and

awe inspiring character. He instituted a

system of instruction for the constables and was rigorous about the importance

of documenting every case. The constables worked twelve-hour days and there was

approximately one constable to every thousand people. In the absence of any

other kind of communication information was passed on at daily meetings between

the constables of neighbouring districts.

The uniform for the constables was similar to contemporary naval dress

and I imagine that Samuel relied upon the experience gained in both his naval

and coast guard appointments. By 1864

there was a total of two hundred men in the Wiltshire Constabulary. Samuel retired in 1870 and apparently towards

the end of his tenure his health had declined and he had become less and less

active. This wasn’t really surprising because he was 76 when he retired. He died three years later. In spite of all the worries about Lydia

Dyer’s health she survived Samuel and lived until her mid eighties.

In her memoir

John Charles

had a large bible with the inscription “To her nephew and Godson John

Charles Thring from his aunt Eliz Anne Jenkyns May 4th 1832”. I

am guessing that it was a present at his Confimation as he was aged 12 at this

time. On the first three blank pages he

wrote his curriculum vitae and other family details. This record shows that he was ordained deacon

in Wells in December 1847; and ordained priest in December 1849. He was curate of Alford with Hornblotton,

where his father was rector and squire, to April 18th 1855. He then went to be curate at Cirencester and

from there to Overton with Fyfield. He

was nearly 34 at the time of the marriage.

The memoir

continues:

“On May 18th

1858 I was married to the Revd. John Charles Thring, at that time curate of

Overton and Fyfield near

My

brother-in- law Edward Thring, the headmaster of

For some

reason this is all that

August 8th

1862

“My brother

certainly is the best fellow alive in his way, for the last night he spoke to

me about my prospects here with a feeling and forbearance wonderfully tender,

considering his views that it is a speculation, and his ignorance of the state

of affairs. I have promised not to buy

anything or borrow again (and please God will keep it faithfully) without

acquainting him, which means of course to me not doing it. He says he is responsible to my other

brothers for my debt. I trust God will preserve us from the trial, but as they

value my blessing, neither my wife nor children must ever accept a penny from

him or the family for anything lost in this cause, I am sure God will not let

them suffer for what I have honestly done in this cause.”

This is one of

many entries relating to Edward’s perennial financial problems in the building

up of

JOHN CHARLES

THRING AND THE RULES OF FOOTBALL

I have another

theory for the reason for the departure of

I have read

several wildly conflicting versions of the origins of the rules of football but

there is no doubt that in 1862 John Charles published his own set of rules

called in one version ‘The Simplest Game’ and in another ‘The Winter Game:

Rules of Football’. I have found a facsimile copy of the cover of the Winter

Game on the internet and the sub heading is “to which are added the rules of

the Cambridge University Committee and London Association.” This version was the 2nd edition

and was printed in early 1863. The

explanation states “in drawing up this amalgamation of the rules formulated up

to this date, Thring became a central figure in the early framing of the laws

of football. This is an important early

document in the history of football, effectively responsible for all that the

game now stands for”. Because of the rise in the number of football clubs the

Football Association was formed in late 1863 and John Charles’s rules in the 2nd

edition of the Winter Game formed the basis from which the Football Association

rules were laid down in December 1863. For me as a non-participant rule number

four of the Simplest Game, “kicks must be aimed only at the ball” seems highly

practical and of prime importance! .

John Charles Thring painted in watercolour by his

daughter Annie in 1900

In 1863, soon

after the formation of the Football Association and without consulting his

brother Edward (the headmaster), John Charles applied for

JOHN CHARLES

THRING – CHAPLAIN TO BRADFORD ON

The

publication of his Winter Game seems to have been the high spot of John

Charles’s career. After another stint as

curate at Alford he went on to become chaplain to the workhouse in Bradford on

Avon[30]

for 16 years but we always got the impression from Great Uncle Ernie that he

thought that his father had rather wasted his talents and was fairly lazy. My father in his own memoir calls John

Charles’s job as chaplain “a sinecure”[31]

but my father would have been influenced strongly by Great Uncle Ernie. The duties of the chaplain were as follows:

§

To

read prayers and preach a sermon to the workhouse inmates every Sunday, and on

Good Friday and Christmas Day

§

To

examine the children, and to catechise such as belong to the Church of England,

and to record the dates of attendance, and the general progress and condition

of the children, and the moral and religious state of the inmates generally.

§

To

visit the sick paupers, and administer religious consolation to them

I imagine that

this job description could entail some very hard work, especially as the

Bradford on

The family

bible not only lists John Charles’s CV and the births and godparents of the

children, it also records their illnesses.

For example:

Whooping

Cough 1867 – Ethel, Meredith, Lionel, Gertrude, Waldron.

Scarlet

Fever July 1870 – Ethel, Lionel, Gertie, Llew, Annie, Gwen.

Typhoid

Fever 1877 April, May and June- Ethel, Meredith, Lionel, Annie, Gwen, Nona,

Hugh Whooping Cough 1879 – Annie,

Gwendoline, Nona, Hugh, Ernest Walsham.

The typhoid

fever episode must have been alarming for all concerned.

THE CHANTRY

HOUSE BRADFORD ON

When searching

the Internet I found a pamphlet called “A Stroll through Bradford on

It is

interesting that although

The Hobhouse family is mentioned in the Life and Letters of Edward

Thring: “The most intimate

holiday playmates of the boys were their cousins of the Hobhouse family, whose

seat, Hadspen, is but a few miles distant from Alford. The relations between the two families seem

to have been particularly affectionate and intimate. One of the Hadspen family remarks in a note:

“I have always reckoned on all Thrings as steadily as brothers, and I never

found them fail yet.” It could be therefore

that Samuel, who purchased the house for

The 1871 census shows both Lydia Dyer (aged

seventy four) and Samuel Meredith (aged seventy seven) living with the large

Thring family at the Chantry House.

Samuel retired in 1870 aged seventy-six and I imagine that when he

bought the Chantry the deal was that he and Lydia Dyer should live there in

retirement.

THE EDUCATION

OF

The education

of the eldest three boys, Meredith, Lionel and Llew was an academic one,

similar to that of their father. They

were sent as boarders to

I know that

Nona,

From letters

to Nona from the principal of

Family lore

has it that the money had run out by the time it was the turn of the two

youngest of the ten children to go on to secondary education. This was why Hugh and Ernest were dispatched

to the Navy as midshipmen[37]

at the age of thirteen and not sent to

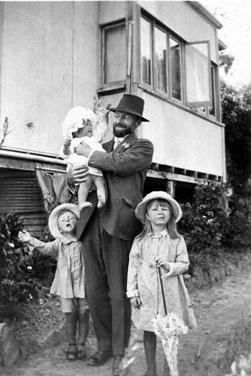

Hugh in his midshipman’s uniform

Although the

experiences of boys in the early days of public schools seem to have been

singularly unpleasant being a midshipman was also very tough indeed; so

probably all

THE LIVES AND

CAREERS OF

The second

child Charles Henry Meredith, known to us as Great Uncle May, made a fortune as

a partner in a scholastic agency called Gabbitas and Thring. The agency found jobs for teachers in

boarding schools. The firm had been set

up in 1873 and Great Uncle May must have joined on coming down from university

in about 1881, becoming a partner fairly soon afterwards. Ronald Searle[38]

produced a lovely cartoon by of two fierce looking gentlemen, one short and one

tall, garbed in black and wearing top hats entitled “Gabbitas and Thring trap a

young man and lead him off to be a master”. An article in The Guardian

newspaper[39]

stated that Gabbitas and Thring were rarely on speaking terms. This is confirmed in my father’s

writings. He says: “When Gabbitas

retired they had a fight in the office about the terms”. Great Uncle May retired soon after this at

the age of 45. He then married an

American actress of about the same age, and they set off on a trip round the

world. He left her in a hotel in

In the early

twentieth century, after both Gabbitas and Thring had departed from the agency,

it recruited a string of writers and poets.

H G Wells, Flecker, W H Auden, John Betjeman and Evelyn Waugh were all

placed in schools by Gabbitas and Thring.

In 1993 the name of Thring was dropped and it is now known only as

Gabbitas. W H Auden wrote a poem in a

letter to a friend in which he referred to it as Rabbitarse and String. At other times it was called “Rabbitguts and

String” and “Grabitall and Fling”.

“String” amuses me, as this was my nickname at school.

My father

reports that in the First World War, in his fifties, Great Uncle May drove an

ambulance in

My father knew

nothing about Ethel (1st child), who died fairly young, but he said

that Gertie (4th child) was a “real sweetie, warm and loving to

my father (Hugh) and Uncle Ernie when they had asthma attacks as boys

and very kind and loving to me. She

suffered from serious ill-health all her life”.

Great Aunt Annie (6th child) was an artist. Family rumour said that she trained at the

Gwen (7th

child) and Nona (8th child) became teachers, and so did Lionel

(3rd child) and Llew (5th child). Gwen was a teacher in

Two references for Nona as she applied for her first job as a teacher

survive:

From W H Young MA Peterhouse

Cambridge Feb 16, 1896

“Miss Nona

Thring, of Newnham College[40],

was my pupil for the three years during which she was preparing for the

Mathematical Tripos of the year 1895.

The distinguished place she took in that examination - one of the four

or five highest that have yet been gained by women candidates - proves that she

has acquired a wide range of mathematical knowledge and a considerable grasp of

mathematical principles. But I am glad

to have an opportunity of adding my testimony to this fact. Miss Thring’s knowledge is in no sense of the

word superficial. All her work has been

thoughtfully and carefully done, and she has on several occasions shown that

she possesses the power of solving problems of decided difficulty. I should like to add that in spending a 4th

year in reading Physics she has been acting partly under my advice, and that I

am convinced that the knowledge she has thus been gaining will prove to be of

immense use to her in teaching mathematics”.

From Katharine

Stephen Vice Principal of

“I have

much pleasure in saying that Miss N A L Thring has been at

She is able

to get on well with other people, and I feel no doubt that she would be liked

as a colleague, and that, owing to her good sense and good nature her help

would be valuable to any Head Mistress under whom she worked. I should expect her to teach with clearness

and brightness, and to be on good terms with her pupils.

I believe

her to be thoroughly conscientious, and to deserve full trust and confidence,

and I have no doubt that she would do her utmost to carry out to the full the

duties of any post that she undertook”.

There are also

two references from Miss Dorothea Beale, the principal of

Feb 13th

1896

“Miss Nona

Thring was a pupil here for 3 years. We

think very highly of her ability, and of her character – and should have

wished, had circumstances permitted it, to place her on our own staff. She has devoted all her time at

Dorothea

Beale Principal”

July 20th

1897

“Miss Nona

Thring was an excellent pupil, and I had always looked forward to engaging her

on our staff, as soon as she had passed her Cambridge examinations, I am sorry

that she decided to leave us at the end of the year, because we had not enough

mathematical work to give her the sort of teaching she wished.

Miss Thring

is not a mere specialist – she has a good knowledge of a larger range of

subjects – she is a good, painstaking and conscientious teacher.

Personally

she is pleasing and one who wins the love and respect of her pupils and

colleagues.

I doubt not

that she will fulfil the expectations of those who have appointed her

Mathematical Mistress at

Nona Thring as a child

The next part

of Nona’s story is told in two personal letters to her from Miss Beale:

June 19th

1900

“Dear Nona

I am so

sorry you have had to give up work for a time – yet perhaps I ought not to say

that – for what is appointed for us must be best – and periods of quiet and

repose are as necessary as those of work.

You have been often in my mind since I heard – I wonder if this is a

touch of influenza .

I wish you

could have come to our Guild – would you care to have the words of the

performance – I have written a preface.

I heard of

your sister from Miss Richardson who was staying with me at Whitsuntide – she

seems very clever as an artist (this must have been Great Aunt Annie) – I hope your sister at

Manchester (I’m not sure who this is; possibly Great Aunt Gwen) is doing

well.

Miss [illegible] is to take up important

work in

I shall

hope to get an improved account of you soon

Yours most

sincerely

Dorothea Beale”

May 3rd

1901

“Dear Nona

It is nice

to hear of your from others – we often think of you, and wish you were well

enough to be with us once more – but now you have to remember that those also

serve, who only stand and wait – I have just been reading [illegible] beautiful life of S.

Francis and it was wonderful what a power he was upon his sick bed – and

the most beautiful sermons I know almost are those Adieux d’A………… [illegible].

I hope you

will enjoy this lovely spring, and read the glorious book [illegible] before us each spring

tide.

I have not

seen your kind uncle for a long time – I may be in

I hear your

sisters are getting on well

With much

sympathy dear Nona, Yours most

sincerely.. Dorothea

Beale”

Nona’ s

illness was terminal and she died at the age of 31 on January 2nd

1902. I wonder if the “kind uncle” was

Lord Henry Thring, the lawyer, as he was the only Thring brother resident in

I cannot

remember my grandfather, Hugh, but I do remember Great Aunt Annie, Great Aunt

Gwen and Great Uncle Ernie. My father

says that Great Uncle Ernie told him that

When we were children we stayed many times with Great Uncle Ernie at his

lovely house on the banks of the river Wylie in Heytesbury in Wiltshire. He was a real Victorian and definitely

believed the Victorian edict that “children should be seen and not heard”. He had piercing blue eyes and we were very

much in awe of him. He became a Captain

in the non-executive branch of the Royal Navy because his eyesight was not good

enough for the executive branch. He was

awarded the Commander of the

As for Hugh, his adult life story features in the Dorothy Wooldridge

section.

THE DEATHS OF

JOHN CHARLES AND

John Charles

died on October 3rd 1909 and a newspaper obituary (probably from the

local paper) says: “he had lived in retirement at the Park Dunmow for the

past ten years and could take very little part in local church affairs, owing

to failing eyesight. One of the rare

occasions upon which he spoke in public was at a meeting of the clergy of the

rural deanery of Dunmow about a year ago, when he protested against the

principles of Socialism which were then advanced. He lived a quiet life, but showed an interest

in parochial affairs, and frequently threw open his grounds for meetings connected

with the church. He had been ill for

four or five months. ……………………He leaves a

widow, five sons, and three daughters.

He was a kind-hearted and generous clergyman and his loss will be

greatly regretted”.

My father

clarifies what happened to

In fact she

died on 4th September 1925.

Pen and ink sketch of

I have a vague impression from my father that, as a grandmother,

THE LIFE OF

When I was eighteen a bank account was opened for me with great

formality at a particular branch of a large bank chain then in Haymarket

London. On each cheque was printed

“Successor to Messrs Stilwell and Sons, Navy Agents and Bankers since 1772”. I was told that all Thrings banked there, as

Stilwells was a family bank. I never

thought to enquire about the family connection.

However when checking the godparents of Lydia and John Charles’ children

I became suspicious that Lydia’s sister Mary featured three times, once as Mary

Meredith, once as Mary D S Meredith and once as Mary D S Stilwell.

Research on the internet revealed all.

Mary lived at home with her parents in Battle House Bromham Wiltshire

until she was 34 and married Henry Stilwell on 16th October 1862

when he was 31. They had two daughters

and three sons but one of the sons died aged eleven. From 1871 Census records they were living in

Melksham Wiltshire; in 1881 they were living in Lancaster Gate London with

Henry listed as a navy agent; in 1891 and 1901 they were in Dorset and Henry is

listed as J.P. for Dorset, retired banker and navy agent. At this stage there were just the two of them

in the house with no fewer that seven servants, a butler, a page, a cook, a

kitchen maid, a lady’s maid, and two housemaids. Mary died aged 75 on 24th June

1901 and in 1907 Henry (aged 73) was married again to a lady aged 58.

IMPORTANT DATES IN THE LIFE OF FLORENCE

Her mother was

Jane Ray born 13th September 1825

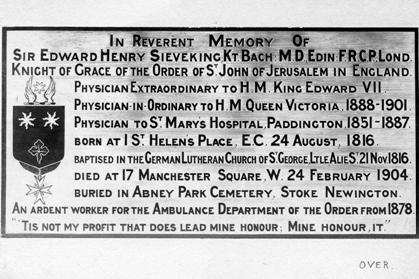

Her father was

Edward Sieveking born 24th August 1816

They married

on 5th September 1849

Her siblings

were:

Henry Edward

born 21st June 1850, died 19th February 1851 aged 8

months

Herbert born

19th April 1853

Arthur born 29th

October 1854

Albert born 17th

July 1857

Henry born 7

December 1859, died October 1873 aged 13 years

Ella born 20th

November 1862

Alexander born

early 1864, died 3rd December 1864 aged 10 months

Emmeline born

1st September 1867

Dorothy

Wooldridge was born 20th January 1887

Leonard died 6th

June 1889

They had four

children:

Muriel born

June 1892

Phyllis born

July 1894

John born

January 1898

Ursula born

November 1900

ELLA’S

On Friday

August 28th 1874 Edward and Jane Sieveking set off for a month’s

holiday with two of their surviving eight children,

While they

were abroad Ella kept a diary, written in beautiful copperplate handwriting. In

it she pasted various menus, restaurant bills, depictions of the hotels they

stayed in, train tickets, newspaper cuttings and pressed flowers. Her spelling and grammar are impeccable apart

from the spelling of a flower, misspelled as “gerainium”. Their holiday was in

In the diary

Ella mentions

THE CAREER OF

EDWARD SIEVEKING

Edward’s own

father was a wool and timber merchant, a descendant of a distinguished

Edward and his

brothers Gustavus and Hermann were born in

In 1863 Edward

was appointed physician in ordinary to the Prince and Princess of

4th

December 1864

Dear Dr

Sieveking

I cannot

tell you how distressed I was to hear of the death of your youngest child, our

godson – which must be a sad blow to yourself and to Mrs Sieveking. I had always understood from you that he had

been so healthy and strong, but the hooping (sic) cough at that tender age is I

believe always more or less dangerous.

The

Princess begs to join me in our sympathy to you and Mrs Sieveking for the sad

loss you have sustained, and although the Almighty has blessed you with a

numerous family, still the loss of an innocent little child is always very

keenly felt. You will be glad to hear

that the Princess and our little boy are very well and enjoying our country

life.

I remain

Yours very

sincerely

Albert

Edward

This letter

was written less than a month after the return of the

In a

commentary on Edward’s diaries by Dr Neville Goodman it is suggested that a

possible reason Edward was eventually spurned by the Wales’s was that he was a

favourite of Victoria, and that she used him as a method of spying on her son

and daughter in law and of trying to influence their medical management. It is known that

Edward’s

diaries are interesting evidence of the changes in medical practice since

Victorian times. After the birth of her

first baby Edward restricted the Princess of Wales “to beef tea with arrowroot,

or vermicelli and marmalade water, she having asked for oranges which we

objected to”. The poor woman must have

been starving! At another time he

recommended she have “stout for luncheon and an earlier dinner hour, 7 instead

of 8”. What sort of medical prescription

is that? Dr Goodman says that quinine

was a sovereign remedy at this time, with few other potent drugs save opium and

aperients. There was in the 1860s no

taking of temperatures, testing of urine, weighing of babies, nor antenatal

care. My own facetious theory for the

spurning of Edward by the

In 1873 Edward

became physician extraordinary[46]

to Queen

Edward

Sieveking wrote numerous medical papers and his best-known monograph was

“Epilepsy and Epileptiform Seizures, their causes, Pathology and

Treatment”. With a colleague he

published a Manual of Pathological Anatomy “Which for many years held its

place as a regular text book in our medical schools.”[47] Apparently it was illustrated with reproductions

of his watercolours. In 1858 he invented